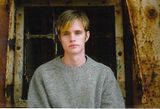

Matthew Shepard

| Matthew Shepard | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | December 1, 1976 Casper, Wyoming |

| Died | October 12, 1998 (aged 21) Fort Collins, Colorado |

| Parents | Judy Peck and Dennis Shepard |

Matthew Wayne Shepard (December 1, 1976 – October 12, 1998) was a 21-year-old student at the University of Wyoming who was tortured and murdered near Laramie, Wyoming, in October 1998. He was attacked on the night of October 6–7, and died at Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins, Colorado, on October 12 from severe head injuries.

During the trial, witnesses stated that Shepard was targeted because he was homosexual. Shepard's murder brought national and international attention to the issue of hate crime legislation at the state and federal levels.[1]

Contents |

Background

Shepard was born in Casper, Wyoming, the oldest of two sons born to Judy Peck and Dennis Shepard. He attended Crest Hill Elementary School, Dean Morgan Junior High School, and Natrona County High School for his freshman through junior years. Saudi Aramco hired his father in the summer of 1994, and his parents subsequently resided at the Saudi Aramco Residential Camp in Dhahran. During that time, Shepard attended The American School in Switzerland (TASIS), [2] from which he graduated in May 1995. Shepard then attended Catawba College in North Carolina and Casper College in Wyoming, before settling in Denver. Shepard became a first-year political science major at the University of Wyoming in Laramie, and was chosen as the student representative for the Wyoming Environmental Council.[1]

He was described by his father as "an optimistic and accepting young man who had a special gift of relating to almost everyone. He was the type of person who was very approachable and always looked to new challenges. Matthew had a great passion for equality and always stood up for the acceptance of people's differences."[1]

In February 1995, during a high school trip to Morocco, Shepard was beaten and raped, causing him to withdraw from school and experience bouts of depression and panic attacks, according to his mother. One of Shepard's friends feared that his depression had driven him to become involved with drugs during his time in college.[3] A few days prior to his death, Shepard had also admitted to a friend, Tim O'Connor, that he was HIV positive and had contemplated committing suicide.[3]

Murder

Shortly after midnight on October 7, 1998, Shepard met Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson at the Fireside Lounge in Laramie, Wyoming. McKinney and Henderson offered Shepard a ride in their car.[4] After Shepard admitted that he was gay, the two men robbed him, pistol whipped, tortured, and tied him to a fence in a remote, rural area, and left him to die. McKinney and Henderson also discovered his address and intended to burgle his home. Still tied to the fence, Shepard was discovered 18 hours later by Aaron Kreifels, who initially mistook Shepard for a scarecrow.[5] At the time of discovery, Shepard was still alive in a coma.

Shepard suffered fractures to the back of his head and in front of his right ear. He experienced severe brain stem damage, which affected his body's ability to regulate heart rate, body temperature and other vital functions. There were also about a dozen small lacerations around his head, face, and neck. His injuries were deemed too severe for doctors to operate. Shepard never regained consciousness and remained on full life support. As he lay in intensive care, candlelight vigils were held by the people of Laramie.[6]

He was pronounced dead at 12:53 a.m. on October 12, 1998, at Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins, Colorado.[7][8][9][10] Police arrested McKinney and Henderson shortly thereafter, finding the bloody gun as well as the victim's shoes and wallet in their truck.[3]

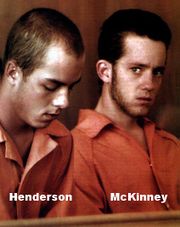

Henderson and McKinney had attempted to persuade their girlfriends to provide alibis.[11]

Trial

At trial, the defendants offered various rationales to justify their actions. They originally pled the gay panic defense, arguing that they were driven to temporary insanity by alleged sexual advances by Shepard. At another point they stated that they had wanted only to rob Shepard and never intended to kill him.[3]

The prosecutor in the case alleged that McKinney and Henderson pretended to be gay in order to gain Shepard's trust to rob him.[12] During the trial, Chastity Pasley and Kristen Price, girlfriends of McKinney and Henderson, testified that Henderson and McKinney both plotted beforehand to rob a gay man. McKinney and Henderson then went to the Fireside Lounge and selected Shepard as their target. McKinney alleged that Shepard asked them for a ride home. After befriending him, they took him to a remote area outside of Laramie where they robbed him, assaulted him severely, and tied him to a fence with a rope from McKinney's truck while Shepard pleaded for his life. Media reports often contained the graphic account of the pistol whipping and his fractured skull. It was reported that Shepard was beaten so brutally that his face was completely covered in blood, except where it had been partially washed clean by his tears.[13][14] Both girlfriends also testified that neither McKinney nor Henderson were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time.[15][16]

Henderson pleaded guilty on April 5, 1999, and agreed to testify against McKinney to avoid the death penalty; he received two consecutive life sentences. The jury in McKinney's trial found him guilty of felony murder. As they began to deliberate on the death penalty, Shepard's parents brokered a deal, resulting in McKinney receiving two consecutive life terms without the possibility of parole.[17]

Henderson and McKinney were incarcerated in the Wyoming State Penitentiary in Rawlins, later being transferred to other prisons because of overcrowding.[18]

Hate crime legislation

Henderson and McKinney were not charged with a hate crime, as no Wyoming criminal statute provided for such a charge. The nature of Matthew Shepard's murder led to requests for new legislation addressing hate crime, urged particularly by those who believed that Shepard was targeted on the basis of his sexual orientation.[19][20] Under then United States federal law[21] and Wyoming state law,[22] crimes committed on the basis of sexual orientation are not prosecutable as hate crimes.

In the following session of the Wyoming Legislature, a bill was introduced defining certain attacks motivated by victim identity as hate crimes, however the measure failed on a 30-30 tie in the Wyoming House of Representatives.[23]

At the federal level, then-President Bill Clinton renewed attempts to extend federal hate crime legislation to include homosexual individuals, women, and people with disabilities. These efforts were rejected by the United States House of Representatives in 1999.[24] In September 2000, both houses of Congress passed such legislation; however it was stripped out in conference committee.[25]

On March 20, 2007, the Matthew Shepard Act (H.R. 1592) was introduced as federal bipartisan legislation in the U.S. Congress, sponsored by Democrat John Conyers with 171 co-sponsors. Shepard's parents were present at the introduction ceremony. The bill passed the House of Representatives on May 3, 2007. Similar legislation passed in the Senate on September 27, 2007[26] (S. 1105), however then-President George W. Bush indicated he might veto the legislation if it reached his desk.[27] The amendment was dropped by the Democratic leadership because of opposition from antiwar Democrats, conservative groups, and Bush.[28]

On December 10, 2007, congressional powers attached bipartisan hate crimes legislation to a Department of Defense Authorization bill, though failed to get it passed. Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the House, said she "is still committed to getting the Matthew Shepard Act passed." Pelosi planned to get the bill passed in early 2008[29] though did not succeed in that plan. Following his election as President, Barack Obama stated that he was committed to passing the Act.[30]

The U.S. House of Representatives debated expansion of hate crimes legislation on April 29, 2009. During the debate, Representative Virginia Foxx of North Carolina called the "hate crime" labeling of Matthew Shepard's murder a "hoax". Matthew Shepard's mother was said to be in the House gallery when the congresswoman made this comment.[31] Foxx later called her comments "a poor choice of words".[32] The House passed the act, designated H.R. 1913, by a vote of 249 to 175.[33] The bill was introduced in the Senate on April 28 by Ted Kennedy, Patrick Leahy, and a bipartisan coalition;[34] it had 43 cosponsors as of June 17, 2009. The Matthew Shepard Act was adopted as an amendment to S.1390 by a vote of 63-28 on July 15, 2009.[35] On October 22, 2009, the act was passed by the Senate by a vote of 68-29.[36] President Obama signed the measure into law on October 28, 2009.[37][38]

Public reaction and aftermath

The anti-gay Westboro Baptist Church of Topeka, Kansas, led by Fred Phelps, picketed Shepard's funeral as well as the trial of his assailants,[39][40] displaying signs with slogans such as "Matt Shepard rots in Hell", "AIDS Kills Fags Dead" and "God Hates Fags".[41] When the Wyoming Supreme Court ruled that it was legal to display any sort of religious message on city property if it was legal for Casper's Ten Commandments display to remain, Phelps attempted and failed to gain city permits in Cheyenne and Casper to build a monument "of marble or granite 5 or 6 feet (1.8 m) in height on which will be a bronze plaque bearing Shepard's picture and the words: "MATTHEW SHEPARD, Entered Hell October 12, 1998, in Defiance of God's Warning: 'Thou shalt not lie with mankind as with womankind; it is abomination.' Leviticus 18:22."[42][43][44][45]

As a counterprotest during Henderson's trial, Romaine Patterson, a friend of Shepard's, organized a group of individuals who assembled in a circle around the Phelps group wearing white robes and gigantic wings (resembling angels) that blocked the protesters. Police had to create a human barrier between the two protest groups.[46] While the organization had no name in the initial demonstration, it has since been ascribed various titles, including 'Angels of Peace' and 'Angel Action'.[39][40] The fence to which Shepard was tied and left to die became an impromptu shrine for visitors, who left notes, flowers, and other mementos. It has since been removed by the land owner.

The murder continued to attract public attention and media coverage long after the trial was over. When ABC 20/20 ran a story in 2004 suggesting that Matthew was HIV positive and quoting claims by McKinney, Henderson and Kristen Price and the prosecutor in the case that the murder had not been motivated by Shepard's sexuality, but rather was a robbery gone violent amongst drug users (the suggestion being that Sheppard was a heavy meth user), [3] it received considerable attention and criticism. Retired Laramie Police Chief Dave O'Malley stated that the murderers' claims were not credible, but the prosecutor in the case stated that there was ample evidence that drugs were at least a factor in the murder.[47] Other coverage focused on how these more recent statements contradicted those made at and near the trial.[48]

Many musicians have written and recorded songs about the murder. Three narrative films and a documentary were made about Shepard: The Laramie Project, The Matthew Shepard Story, Anatomy of a Hate Crime and Laramie Inside Out, and Moral Obligations, a fictionalized account of the night of the murder. The Laramie Project is also often performed as a play. The play involves recounts of interviews with citizens of the town of Laramie ranging from a few months after the attack to a few years after. The play is designed to display the town's reaction to the crime.[49][50] Ten years later, The Laramie Project created a second play, based on interviews with members of the town, Shepard's mother, and his incarcerated murderer.[51]

In the years following Shepard's death, his mother Judy has become a well-known advocate for LGBT rights, particularly issues relating to gay youth. She is a prime force behind the Matthew Shepard Foundation, which supports diversity and tolerance in youth organizations.

Further reading

- Shepard, Judy; (2009). The Meaning of Matthew: My Son's Murder in Laramie, and a World Transformed. New York, NY: Penguin Group USA. ISBN 9781594630576.

- Campbell, Shannon; Laura Castaneda (2005). News and Sexuality: Media Portraits of Diversity. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications, Inc. ISBN 1412909988.

- Fondakowski, Leigh; Kaufman, Moises (2001). The Laramie project. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 0375727191.

- Garceau, Dee; Basso, Matthew; McCall, Laura (2001). Across the Great Divide: cultures of manhood in the American West. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0415924715.

- Hinds, Patrick; Romaine Patterson (2005). The Whole World Was Watching: Living in the Light of Matthew Shepard. Advocate Books. ISBN 1555839010.

- Loffreda, Beth (2000). Losing Matt Shepard: life and politics in the aftermath of anti-gay murder. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231118597.

- Swigonski, Mary E.; Mama, Robin S.; Ward, Kelly (2001). From Hate Crimes to Human Rights: A Tribute to Matthew Shepard. New York: Routledge. ISBN 1560232560.

- "The Laramie project" by Moises Kaufman

See also

- Violence against LGBT people

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Matthew Shepard Foundation webpage". Matthew Shepard Foundation. http://www.matthewshepard.org/site/PageServer. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ↑ Julie Cart (September 14, 1999). "Matthew Shepard's Mother Aims to Speak With His Voice". Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/1999/sep/14/news/mn-9950?pg=2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "New Details Emerge in Matthew Shepard Murder". ABC News Internet Ventures. November 26, 2004. http://abcnews.go.com/2020/Story?id=277685&page=1. Retrieved 2009-06-07.

- ↑ "Killer: Shepard Didn't Make Advances". Salon.com. http://dir.salon.com/story/news/feature/1999/11/06/witness/index.html. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- ↑ Hughes, Jim (15 October 1998). "Wyo. cyclist recalls tragic discovery". The Denver Post (Denver: The Denver Post). http://www.texasdude.com/related.htm.

- ↑ "University of Wyoming Matthew Shepard Resource Site". University of Wyoming. http://www.uwyo.edu/News/shepard/. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ↑ "Murder charges planned in beating death of gay student". CNN. October 12, 1998. http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.03/index.html. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ↑ Lacayo, Richard (October 26, 1998). [http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989406,00.html "The New Struggle"]. Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,989406,00.html. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ↑ "Beaten gay student dies; murder charges planned". CNN. October 12, 1998. http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/12/wyoming.attack.02/index.html. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ↑ "Matthew Shepard Medical Update" (PDF). PVHS. October 12, 1998. https://vic.pvhs.org/pls/portal/docs/PAGE/PVHS/PVHS_DOCUMENT_MGMT2/NEWS_REPOSITORY/MATTHEW%20SHEPARD%20MEDICAL%20UPDATE.PDF. Retrieved 2007-01-14.

- ↑ "New details emerge about suspects in gay attack". CNN.com (Cable News Network). 13 October 1998. Archived from the original on 2008-05-08. http://web.archive.org/web/20080508011253/http://www.cnn.com/US/9810/13/wyoming.attack.02/index.html. Retrieved 21 January 2007.

- ↑ Tuma, Clara, and The Associated Press (April 5, 1999). "Henderson pleads guilty to felony murder in Matthew Shepard case". Court TV. http://www.courttv.com/archive/trials/henderson/040599_pm_ctv.html. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ Loffreda, Beth (2000). Losing Matt Shepard: life and politics in the aftermath of anti-gay murder. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231118589. http://www.nytimes.com/books/first/l/loffreda-shepard.html.

- ↑ Chiasson, Lloyd (November 30, 2003). Illusive Shadows: Justice, Media, and Socially Significant American Trials. Praeger. p. 183. ISBN 9780275975074.

- ↑ "The Daily Camera:Matthew Shepard Murder". Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. http://web.archive.org/web/20080424091724/http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ Black, Robert W. (October 29, 1999). "Girlfriend: McKinney told of killing". The Daily Camera. http://homes.thedailycamera.com/extra/shepard/29bshep.html.

- ↑ Cart, Julie (November 05, 1999). "Killer of Gay Student Is Spared Death Penalty; Courts: Matthew Shepard's father says life in prison shows 'mercy to someone who refused to show any mercy.'". Los Angeles Times: p. A1.

- ↑ Torkelson, Jean (3 October 2008). "Mother's mission: Matthew Shepard's death changes things". Rocky Mountain News (The E.W. Scripps Co.). http://m.rockymountainnews.com/news/2008/oct/03/10-years-later-matthew-shepard-hasnt-been-forgotte/. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ↑ Colby College (March 7, 2006). "Mother of Hate-Crime Victim to Speak at Colby". http://www.colby.edu/news/detail/612/. Retrieved 2006-04-06. Press release.

- ↑ "Open phones". Talk of the Nation (National Public Radio). October 12, 1998. http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1009867. Retrieved 2006-04-06. "Denounced nationwide as a hate crime" at 1:40 elapsed time.

- ↑ "Investigative Programs: Civil Rights: Hate Crimes". Federal Bureau of Investigation. http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ "Map of State Statutes". Anti-Defamation League. http://www.adl.org/99hatecrime/provisions.asp. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ Blanchard, Robert O. (May 1999). "The "Hate State" Myth". Reason. http://reason.com/9905/fe.rb.the.shtml. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ Barrett, Ted, and The Associated Press (September 13, 2000). "President Clinton urges Congress to pass hate crimes bill: GOP aides predict legislation will pass House, but will not become law". CNN. http://transcripts.cnn.com/2000/ALLPOLITICS/stories/09/13/hate.crimes/index.html. Retrieved 2006-04-07.

- ↑ Office of House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi (October 7, 2004). "House Democrats Condemn GOP Rejection of Hate Crimes Legislation". http://democraticleader.house.gov/press/releases.cfm?pressReleaseID=718. Retrieved 2006-04-07. Press release.

- ↑ Simon, R. Bush threatens to veto expansion of hate-crime law, Los Angeles Times, 2007-05-03. Retrieved on 2007-05-03.

- ↑ Stout, D. House Votes to Expand Hate Crime Protection, New York Times, 2007-05-03. Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ↑ Wooten, Amy (January 1, 2008). "Congress Drops Hate-Crimes Bill". Windy City Times. http://www.windycitymediagroup.com/gay/lesbian/news/ARTICLE.php?AID=17078. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ↑ Caving in on Hate Crimes, New York Times, 2007-12-10. Retrieved 2007-12-11.

- ↑ Lynsen, Joshua (13 June 2008). "Obama renews commitment to gay issues". Washington Blade (Window Media LLC Productions). http://www.washblade.com/2008/6-13/news/national/12766.cfm. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

- ↑ Grim, Ryan (April 29, 2009). "Virginia Foxx: Story of Matthew Shepard's Murder A "Hoax"". Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/04/29/virginia-foxx-story-of-ma_n_192971.html. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ↑ "Congresswoman calls gay death case a `hoax'". http://abclocal.go.com/wtvd/story?section=news/local&id=6788587. Retrieved 2009-04-29.

- ↑ Stout, David (April 29, 2009). "House Passes Hate-Crimes Bill". New York Times. http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/04/29/house-passes-hate-crimes-bill/. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ "Matthew Shepard Hate Crimes Prevention Act Introduced in Senate". Feminist.org. 2009-04-29. http://www.feminist.org/news/newsbyte/uswirestory.asp?id=11668. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate: Legislation & Records Home > Votes > Roll Call Vote:". http://www.senate.gov/legislative/LIS/roll_call_lists/roll_call_vote_cfm.cfm?congress=111&session=1&vote=00233/. Retrieved 2009-07-17.

- ↑ Roxana Tiron, "Senate OKs defense bill, 68-29," The Hill, found at The Hill website. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ↑ Pershing, Ben (23 October 2009). "Senate passes measure that would protect gays". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/10/22/AR2009102204689.html.

- ↑ Geen, Jessica (October 28, 2009). "Mother of Matthew Shepard welcomes US hate crimes bill". Pink News. http://www.pinknews.co.uk/2009/10/28/mother-of-matthew-shepard-welcomes-us-hate-crimes-bill. Retrieved 2009-10-28.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Suspect pleads guilty in beating death of gay college student". CNN. April 05, 1999. http://www.cnn.com/US/9904/05/gay.attack.trail.02/. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "The Whole World Was Watching". http://www.paraview.com/patterson/index.htm. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ "Matthew Shepard Online Resources - Hate Speech - Rev. Fred Phelps". http://www.hatecrime.org/subpages/hatespeech/phelps.html. Retrieved 2007-01-18.

- ↑ Sink, Mindy (October 30, 2003). "Wyoming: Council Votes To Move Ten Commandments From Park". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9905E6DB1430F933A05753C1A9659C8B63. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ Kelly, David (October 12, 2003). "The Nation; Intolerance Chiseled in Stone Hits City Hard; Casper, Wyo., faces the prospect of having to allow a monument that condemns gay murder victim Matthew Shepard". Los Angeles Times: p. A20.

- ↑ "Monument dedicated to Matthew Shepard's Entry Into Hell, which WBC intends to erect in Casper City Park as a solemn Memorial that God Hates Fags & Fag-Enablers". Westboro Baptist Church. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. http://web.archive.org/web/20071020072550/http://www.godhatesfags.com/main/shepard_monument.html. Retrieved 2006-04-06. Page includes picture of proposed monument.

- ↑ Burke, Brendan (October 3, 2003). "Phelps seeks anti-gay marker". Casper Star-Tribune. http://www.casperstartribune.net/articles/2003/10/03/news/casper/f060e8d5f0ddf401c07f72e2617c79c6.txt. Retrieved 2006-04-06.

- ↑ "Suspect pleads guilty in beating death of gay college student". CNN.com (Cable News Network). 5 April 1999. http://www.cnn.com/US/9904/05/gay.attack.trail.02/. Retrieved 21 January 2007.

- ↑ Knittel, Shaun. "The Matthew Shepard paradox: How one U.S. Representative opened hate's old wounds". sgn.org. Seattle Gay News. http://www.sgn.org/sgnnews37_20/mobile/page1.cfm. Retrieved October 29, 2009.

- ↑ "Rewriting the Motives Behind Matthew Shepard’s Murder". [1]. December 8, 2004. http://journalism.nyu.edu/pubzone/recount/article/95/. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ↑ Hart, Dave (November 12, 2008). "The Laramie Project". The Chapel Hill News. The News & Observer Publishing Company. http://www.chapelhillnews.com/news/story/25210.html. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ↑ Hugenberg, Jenny (February 14, 2008). "Gay-themed high school play draws protest, support". Kalamazoo Gazette. http://www.mlive.com/news/index.ssf/2008/02/kalamazoo_a_group_has.html. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ↑ "Remembering a Cruel Murder: Laramie Revisited". Thefastertimes.com. 2009-10-04. http://thefastertimes.com/theatertalk/2009/10/04/333/. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

External links

- The Matthew Shepard Foundation (official website)– founded by parents Judy and Dennis Shepard to "Replace hate with understanding, compassion, and acceptance through educational, outreach, and advocacy programs and by continuing to tell Matthew's story"

- ABC News - 2004 Report on the Attack, a "Third Story", and the Trials

- Criminal complaint against McKinney and Henderson

- Website for biography "The Whole World Was Watching: Living In The Light of Matthew Shepard"

- Matthew Shepard Resource Site at the University of Wyoming;

- Matthew Shepard Online Resources

- Barry Yeoman, A Mother Finds Her Voice, US Weekly

- Laramie Inside Out Documentary Film

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||